History of the Manchurian Pheasant Project

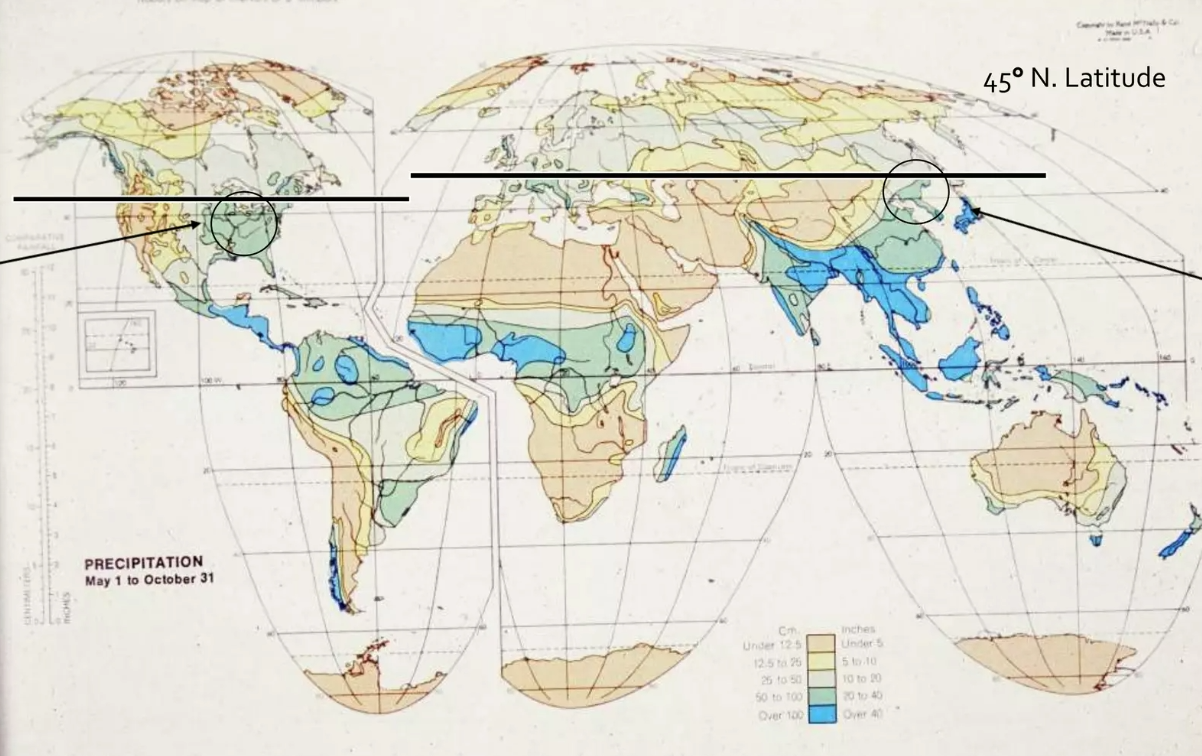

After three years of planning and the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture’s assistance, we imported a shipment of Ringneck pheasant eggs from China in June of 1989. Bill MacFarlane traveled to Jilin Province, near Changchun City to collect the eggs. This provience is located in Northeast China, north of North Korea. After research, we felt pheasants imported from Jilin would fare well in Wisconsin since this is located at hte same latitude and has a simlar average temperature and seasons throughout the year.

The shipment of eggs arrived in Beijing airport one day after the massacre at Tianaman Square, and sat at the airport for one week before finally proceeding. By the time the shipment arrived in Chicago, some of the eggs were one month old. We were concerned whether any of the 1,200 eggs would hatch. We were ecstatic when 25 days later we had over 400 newly hatched truly Chinese pheasants!

After exhaustive testing (over 300 separate samples were taken) and a 30-day waiting period, APHIS (a U.S. government department responsible for regulating the importation of plants and animals into the U. S.) declared the chicks to be completely healthy and released them from the quarantine facility to be brought to our farm. We built a new brooder house and pen for them one mile from our main farm and there they have thrived.

The birds were all that we had hoped for and more – their size and appearance was similar to what we had sold for years as a Chinese Ringneck, whereas their behavior appeared to us to be much more wild.

There are a few distinctions in appearance, though. The cock pheasants’ rings are broader than most any pheasants we have seen, and the cocks also have a small distinctive white feather on the sides of their heads near the ear. Their saddles are blue-green, and their flanks are yellow like the birds we have had for years.

There are a few distinctions in appearance, though. The cock pheasants’ rings are broader than most any pheasants we have seen, and the cocks also have a small distinctive white feather on the sides of their heads near the ear. Their saddles are blue-green, and their flanks are yellow like the birds we have had for years.

The hens are similar in size and shape to our hens, but their color is more golden and their heads are different in conformation. Both the hens and cocks have a very erect posture, similar to an Afghan-Whitewing. The birds are very skittish (even when they were just a few days old they ran to the far corner of the brooder house when someone opened the door) and they flush repeatedly when you enter their pen.

Jean Delacour’s book, The Pheasants of the World lists the name of our bird as Phasianus colchicus pallasi or Manchurian Ring-necked pheasant. We were successful in importing another shipment of Manchurian Ringneck eggs from China in 1990. We had a release here on our farm of pure strain Manchurian Ringnecks – but it wasn’t planned!

On December 3, 1990, a strong blizzard occurred, and it blew a gate off our Manchurian pen. When the blizzard subsided, we discovered that about 500 of the 800 pheasants in the pens had escaped. We were lucky to catch 300 over the next few days, but the remaining 200 have rebuffed our repeated attempts at capture. They are surviving well. We learned more about their behavior through this experience. We found that they roost in trees at night and also got repeated first-hand glances at their powerful flight.

In 1990, we sold a cross of the pure Manchurian Ringneck cocks and our own Ringneck hens. We sold over 20,000 of these chicks and have had only positive responses. We also kept about 20,000 of these hybrid chicks to be raised and sold as mature birds. We found that the cross produced a very hardy, vigorous bird – and that the wildness was very apparent when they were chicks and when they were grown.

Since 1990, over the past 20 years we have sold hundreds of thousands of Manchurian Cross pheasant chicks . One of our biggest markets is the U.K. We have maintained a pure flock of Manchurian pheasants which we use to cross with our own pheasants. We have the only pure flock of Manchurian pheasants.